Acute respiratory tract infections (ARTIs) are an important cause of morbidity and mortality among children under the age of 5 years [1,2], with the highest number of deaths occurring in developing countries [3]. In China, pneumonia is the leading cause of deaths in children under 5 years old with an estimated >30 000 deaths annually [4]. Viruses have been considered as the most frequent causes of ARTIs. The predominant viruses associated with ARTIs in children include respiratory syncytial virus (RSV), influenza virus (IV), parainfluenza virus (PIV), human rhinovirus (HRV) and adenovirus (ADV) [5,6].

RSV is the leading cause of ARTIs in early childhood. It is estimated that 33.8 million new episodes of RSV–associated ALRI occurred worldwide in children younger than 5 years, with at least 3.4 million episodes representing severe RSV–associated acute lower respiratory infection (ALRI) necessitating hospital admission [7]. The pattern of RSV infections is variable and related to season, socio–demographic and characteristics of study populations.

China has the largest child population and has substantial differences in climate from region to region. It has a variety of temperature and rainfall zones, including continental monsoon areas. The total population of children aged 14 years or younger is estimated to be 230 million. Although the epidemiology of RSV infections has been studied in cities such as Beijing, Chongqing and Lanzhou [8–10], few RSV studies in China have been published in English. Therefore, we performed a systematic review and meta–analysis of published studies to evaluate the epidemiology of RSV infections in patients with ARTIs.

A better understanding of the epidemiology of RSV infections plays a key role for the prevention, control and treatment of ARTIs. The objective of this systematic review and meta–analysis was to evaluate the etiology, serotypes, clinical features, age distribution and seasonality associated with RSV infections in China.

Search strategy

A systematic search was performed in indexed databases, including Chinese BioMedical Database (CBM), China National Knowledge Infrastructure (CNKI), Wanfang database and PubMed to identify available RSV studies in China. The following search terms were used: RSV or syncytial virus. Taking into account the quality of studies, high quality publications from the Chinese core journals (2014 edition) [11] were considered in the final analysis. The Library of Perking University evaluates all Chinese journals every four years and excludes lower quality journals using the quality measurement similar to the impact factors. To obtain recent data, the search strategy was limited to publications dated from January 2010 to Mar 2015. Details of the search strategy are presented in Appendix S1 in Online Supplementary Document(Online Supplementary Document) .

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

To be included, the following criteria had to be fulfilled: 1) studies in humans; 2) studies in patients with ARTIs; 3) studies that had at least one following outcome: etiology of acute respiratory infections; seasonality; gender; age group; serotypes; clinical features; 4) studies published in Chinese or English.

Publications were excluded if they were: 1) animal experiments or basic research (examples, studies focus on principles or mechanisms using cells and tissues); 2) case reports, systematic review or meta–analysis; 3) replicates (when the same population was studied in more than one publication, only the latest one or the one with the most complete data was considered for the meta–analysis).

ARTIs was defined as patients who were present of one or more respiratory symptoms, including watery eyes, rhinorrhea, nasal congestion or sinus congestion, otitis media, pharyngitis, cough, sore throat, sneezing, headache, and muscle pain. Meanwhile, patients had at least one symptom during acute infection, with high fever (body temperature ≥38°C) or chillness or normal/low leukocyte count or who were diagnosed with pneumonia by chest radiography previously. Chest radiography was conducted according to the clinical situation of the patient, and pneumonia was defined as an acute illness with radiographic pulmonary shadowing (at least segmental or in one lobe) by chest radiography.

Literature screening and data extraction

Literature reviewers were divided into two parallel groups. Using the set criteria of inclusion and exclusion, the reviewers independently screened the literature by title, keyword and abstract. Any disagreement was solved by a third reviewer. If they were not sure whether the study should be included, the decision was made based on further review of the full texts. NoteExpress 2 (Aegean Software Corporation, Shanghai, China) was used for the bibliography management.

Two parallel groups independently extracted the following data from eligible studies: general information, methodological quality and outcome data. Inconsistencies between two groups were checked after data extraction. Any disagreements were solved by the third reviewer.

Quality assessment

This meta–analysis included various types of studies with different outcomes. Therefore, no pre–existing scale is directly suitable for the assessment. The 5–item specific rating scale was developed to assess the quality of studies. These included 1) Did the study report patients’ information? 2) Did the study report diagnosis criteria of acute respiratory infection? 3) Did the study report specimen collection methods? 4) Did the study report pathogen detection methods? 5) Did the study report statistical methods? Each item was scored on three scales; 0 indicating low quality, 1 indicating medium quality, and 2 indicating high quality. The score for each item was then added to give a composite score for the study, with a highest total score of 10. If the total score was equal to or greater than 8, we regarded the study as “good” quality.

Statistical analysis

The MetaAnalyst (Beta 3.13; Tufts Evidence–based Practice Center, Boston, USA) was used to conduct meta–analyses for pooled proportions and odds ratios. Considering heterogeneity across all studies, we chose a random–effects model to carry out meta–analysis using Der–Simonian Laird method. The publication bias was determined via Stata 12.0 (StataCorp LP, Texas, USA) using an Egger’s test. Meta–analysis for combining the results of studies was weighted to provide the balanced results of all included studies.

Selection of studies

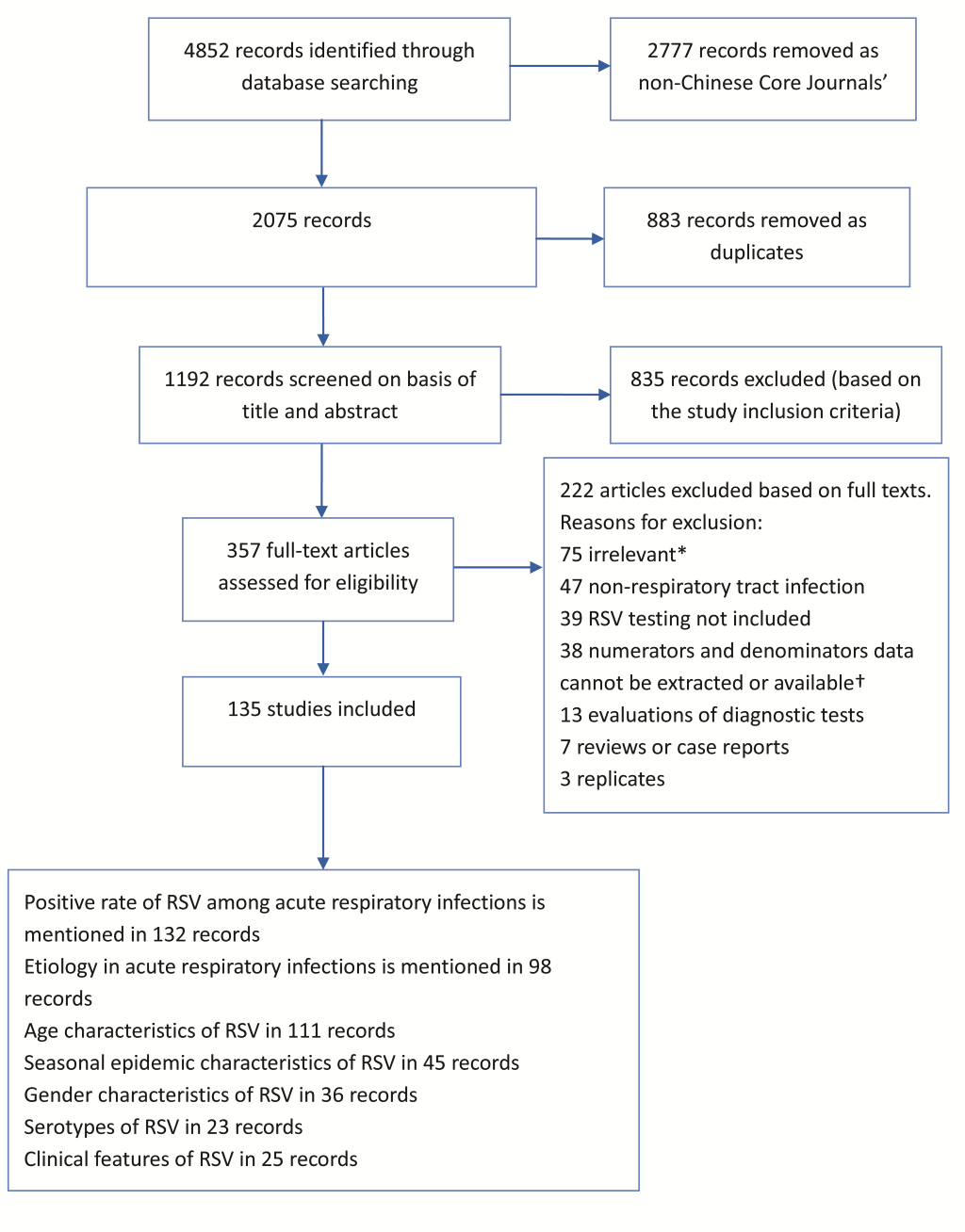

Of the total of 4852 studies identified through the databases, 135 studies were included in the analysis ( Figure 1 ). Of the 135 studies, 123 studies were in children less than 16 years old and the remaining studies were in both children and adults. Of the 135 studies, 19 studies were published in English. The detailed information about author, publication year, province, age, specimen type, detection methodology, number of specimen and study outcomes are listed in Appendix S2 in Online Supplementary Document(Online Supplementary Document) .

For the 135 studies, the quality evaluation score ranged from 5 to 10 points, with a mean ± standard deviation of 7.7 ± 1.3. There were 80 studies with a score of ≥8. The summary of quality assessment is listed in Appendix S3 in Online Supplementary Document(Online Supplementary Document) .

Etiology

The overall positivity rate of RSV among patients with ARTIs was 18.7% (95% CI 17.1–20.5%), followed by HRV, human bocavirus (HBoV), IV, PIV, human metapneumovirus (HMPV), enterovirus, ADV and human coronavirus (HCoV). ( Table 1 ).

| Virus | No. articles included | Virus–positive | Total patients | Positive rate (%, 95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| RSV | 132 | 81 747 | 489 641 | 18.7 (17.1–20.5) |

| Rhinovirus | 36 | 3647 | 31 605 | 11.5 (9.8–13.5) |

| HBoV | 45 | 5899 | 110 345 | 6.8 (5.5–8.5) |

| IV | 95 | 17 115 | 262 089 | 6.5 (5.4–7.7) |

| PIV | 97 | 17 515 | 264 538 | 6.4 (5.6–7.2) |

| HMPV | 59 | 5935 | 130 620 | 4.3 (3.6–5.1) |

| Enterovirus | 16 | 923 | 17 689 | 4.0 (2.8–5.6) |

| Adenovirus | 96 | 9618 | 275 380 | 3.4 (2.9–3.9) |

| HCoV | 39 | 1544 | 66 048 | 2.6 (2.0–3.4) |

RSV – respiratory syncytial virus, PIV – parainfluenza virus, IV – influenza virus, HMPV – human metapneumovirus, HBoV – human bocavirus; HCoV, Human coronavirus, CI – confidence interval

The prevalence of RSV was stratified into inpatients, outpatients, inpatients/outpatients and unknown category. RSV was found most frequently among inpatients 22.0% (95% CI 19.9–24.2%), followed by inpatients/outpatients, outpatients and unknown ( Table 2 ).

| No. articles included | Virus–positive | Total patients | Positive rate (%, 95% CI) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Settings: | ||||

| Inpatient | 86 | 67 319 | 366 386 | 22.0 (19.9–24.2) |

| Outpatient | 9 | 1061 | 9229 | 14.0 (9.6–19.9) |

| Inpatient/outpatient | 45 | 8779 | 67 826 | 15.8 (12.1–20.2) |

| Unspecified | 95 | 4568 | 46 200 | 11.4 (7.4–17.1) |

| Total | 132 | 81 747 | 489 641 | 18.7 (17.1–20.5) |

| Age groups: | ||||

| 0–6m | 45 | 12 522 | 43 222 | 29.9 (26.2–33.8) |

| 0–1y | 65 | 29 607 | 113 386 | 26.5 (23.7–29.5) |

| 0–3y | 55 | 27 544 | 130 152 | 23.7 (20.9–26.9) |

| 0–6y | 47 | 17 854 | 121 717 | 19.5 (16.0–19.6) |

| 0–16y | 72 | 57 193 | 351 426 | 17.7 (5.5–8.5) |

| ≥16y | 7 | 440 | 18 781 | 2.8 (1.3–6.1) |

| Inpatients only by age groups: | ||||

| 0–6m | 31 | 10 690 | 35 592 | 32.4 (27.7–37.4) |

| 0–1y | 44 | 25 259 | 97 542 | 34.4 (28.9–40.4) |

| 0–3y | 37 | 20 789 | 99 951 | 24.3 (20.6–28.3) |

| 0–6y | 28 | 12 446 | 88 248 | 19.8 (16.4–23.7) |

| 0–16y | 45 | 46 128 | 270 359 | 20.0 (17.9–22.3) |

| ≥16y | 3 | 174 | 8604 | 2.8 (0.8–9.8) |

| Regions: | ||||

| Northeast | 2 | 285 | 3003 | 9.5 (8.5–10.6) |

| North China | 18 | 2203 | 26 710 | 10.9 (6.3–18.4) |

| South China | 23 | 10 625 | 96 413 | 15.7 (13.2–18.6) |

| East China | 44 | 50 001 | 273 312 | 17.6 (15.3–20.2) |

| Central China | 14 | 2978 | 16 346 | 22.5 (16.8–29.5) |

| Northwest | 9 | 1523 | 5010 | 27.6 (21.3–34.9) |

| Southwest | 20 | 10 375 | 35 970 | 28.7 (25.7–32.0) |

| Multi–regions | 2 | 3757 | 32 877 | 14.7 (6.6–29.6) |

| Detection methodology* | ||||

| IF | 51 | 41 201 | 230 033 | 17.0 (14.4–20.0) |

| PCR | 73 | 32 814 | 201 063 | 19.9 (17.9–22.1) |

| Others | 8 | 7732 | 58 545 | 20.1 (15.8–25.3) |

*PCR – polymerase chain reaction, IF – immunofluorescence, Others – refers to PCR/IF and RVP Fast, y – year, m – month, CI – confidence interval

Seasonal characteristics

A total of 45 studies reported the seasonality of RSV infections. Of these 45 studies, 28 studies reported monthly isolation rates and the remaining 17 studies reported quarterly. The peak of RSV infections mainly occurred in winter and spring ( Table 3 ).

| Month/season* | No. articles included | RSV–positive | Total patients | Positive rate (%) (95% confidence interval) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Jan | 17 | 1150 | 4672 | 24.7 (15.2–37.5) |

| Feb | 17 | 1094 | 4311 | 25.1 (17.1–35.4) |

| Mar | 17 | 849 | 4003 | 19.5 (13.5–27.4) |

| Apr | 16 | 504 | 3174 | 17.4 (13.5–22.3) |

| May | 15 | 181 | 2551 | 8.7 (6.1–12.3) |

| Jun | 14 | 135 | 2945 | 5.5 (3.1–9.4) |

| Jul | 14 | 105 | 2805 | 4.5 (3.–6.8) |

| Aug | 13 | 163 | 2605 | 7.0 (4.5–10.7) |

| Sep | 14 | 183 | 2511 | 6.4 (3.6–11.3) |

| Oct | 16 | 254 | 2935 | 7.5 (4.2–13.1) |

| Nov | 17 | 597 | 3522 | 14.4 (8.8–22.5) |

| Dec | 17 | 1049 | 3954 | 26.2 (17.9–36.8) |

| Spring | 27 | 5627 | 37 738 | 13.9 (11.1–17.4) |

| Summer | 27 | 2008 | 31 716 | 5.3 (3.7–7.6) |

| Autumn | 27 | 4204 | 28 223 | 11.8 (8.2–16.8) |

| Winter | 27 | 9774 | 32 937 | 22.7 (17.4–29.1) |

*Spring – 1 March to 31 May, Summer – 1 June to 31 August, Autumn – 1 September to 30 November, Winter – 1 December to 28/29 February.

Gender characteristics

A total of 36 studies reported gender characteristics of RSV infections. Among 96 694 male patients, RSV was positive in 17 163 patients (20.4%, 95% CI 16.6–24.8%). Among 54 958 female patients, RSV was positive in 8364 (19.9%, 95% CI 16.0–24.4%).

RSV serotypes

There were 23 studies that reported RSV serotypes. Among 4172 RSV infected patients; type A, type B and mixed type A and B were detected in 2469 (63.1%, 95% CI 52.3–72.8%), 1611 (35.6%, 95% CI –6.0 to –46.6%) and 92 (1.2%, 95% CI 0.7–2.2%), respectively.

Clinical characteristics

Twenty–five studies reported the clinical manifestations of RSV infection. The most frequently reported clinical manifestations were cough, sputum production, wheezing and fever ( Table 4 ).

| Clinical characteristics | No. articles included | Symptomatic patients | RSV infected patients | Percent (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cough | 24 | 9880 | 11 194 | 93.9 (91.0–96.0) |

| Expectoration | 6 | 1578 | 2316 | 66.3 (43.8–83.2) |

| Wheeze | 13 | 1768 | 2778 | 65.7 (56.5–73.8) |

| Fever | 22 | 3738 | 10 018 | 43.0 (37.5–48.7) |

| Rhinorrhea | 8 | 1621 | 5669 | 42.7 (31.6–54.6) |

| Cyanosis | 9 | 1346 | 4318 | 38.9 (15.8–68.2) |

| Tachypnea | 11 | 2024 | 7737 | 32.2 (15.7–54.9) |

| Diarrhea | 7 | 838 | 5272 | 18.8 (11.4–29.5) |

| Dyspnoea | 8 | 1707 | 7918 | 12.8 (5.0–28.9) |

Sensitivity analysis and publication bias

The conclusions remained robust and the outcomes did not alter significantly when only ‘good’ quality studies were evaluated in the sensitivity analysis. The overall RSV positivity rates were 19.7% (95% CI 17.7–21.9%) in all patients (n = 79), 22.7% (95% CI 20.2–25.3%) in inpatients (n = 53), and 13.8% (95% CI 8.3–22.0%) in outpatients (n = 5).

Publication bias was tested using the Egger’s test. No publication bias was detected when verifying the 132 publications that reported RSV positive rates in all patients (–0.27, 95% CI –1.19 to –0.65, P = 0.563).

RSV is the most common viral cause of ARTIs in developed and developing countries [7,12]. However, the available epidemiological data on RSV in China has not been systematically summarized in English. Our results highlight that RSV is the leading cause of viral ARTIs in China.

The burden of respiratory viral infections is difficult to measure and is likely to differ from country to country due to several factors such as socio–demographic distribution, seasonal variation, study design and diagnostic techniques. In our study, RSV was the most frequently detected pathogen among patients with ARTIs in all age groups studied. Consistent with other studies, RSV and HRV were the most prevalent viruses in children [2,13,14].

In the present study, only 12 studies reported the RSV infections in adult patients and the remaining 123 studies were in children. Infants aged ≤1 year were at higher risk of RSV associated ARTIs, compared with those in other age groups. This is consistent with the previous reports of RSV in both developed and developing countries [7,12,15,16]. The data show that RSV accounted for nearly 30% of all ARTIs in infants. Efforts to prevent RSV infections in infants can lead to a substantial reduction of RSV associated morbidity, mortality and medical costs in China. Further evidence of RSV disease burden can be established by adding RSV studies in existing influenza surveillance systems.

The relation between RSV infections and climate has been well documented [17,18]. In regions with persistently warm temperatures and high humidity, RSV activity is continuous throughout the year, peaking in summer and early autumn. In temperate climates, RSV activity is maximal during winter, correlating with lower temperatures. In areas where temperatures remain colder throughout the year, RSV activity also occurs almost continuously [17,18]. Most areas of China have a temperate climate. We found that the peak of RSV activity mainly occurred during winter and spring in China, which is similar to the previous reports [19–21]. This pattern of seasonality corresponds to the cold and dry seasons. However, we are unable to report regional differences in RSV activity due to limited data availability.

Based on genetic and antigenic variations in structural proteins, RSV isolates are subdivided into two major antigenic types (A and B). Both types are associated with mild to severe ARTIs [22–24]. Studies have shown that type A and B viruses co–circulate in the same area during epidemic periods and have various patterns of predominance [25–28]. However, the prevalence of each type may shift yearly and can vary among different communities [28–30]. Our analysis showed that type A was the predominant serotype accounting for 63.1% of all RSV infections. However, it is difficult to know how the sero–epidemiological trend changed in the recent years in China. This is because the study periods and locations varied substantially among included studies.

The studies we included differed in their methods of sampling and case–definition. Therefore, caution should be taken when interpreting the results. In our study, only 42 studies presented detailed criteria for case–definition. In addition, only 54 out of the 135 included studies used immunofluorescence for RSV detection. RSV was identified less frequently (17.0%) if only the results of studies based on immunofluorescent detection were included. In comparison with immunofluorescence, molecular diagnostics are more sensitive and specific [31,32]. In recent years, the introduction of nucleic acid based diagnostic tests has markedly improved our understanding of viral etiology among ARTI patients [33]. Therefore, the real burden of RSV in China is likely to be higher than our findings if more sensitive diagnostic methods are used.

These differences in case definitions and diagnostic techniques are likely to have impacted the results. Therefore, a random effects model was applied to take into account the heterogeneity between studies resulting in wider 95% CIs with more conservative estimates of the overall results [34]. In addition, the etiology data in the present study should be interpreted with caution. This is because restricting RSV to the title and abstract in the search criteria is a potential source of bias and might not be representative of all studies reporting other viruses. However, all included studies in current review tested for multiple viruses. Therefore, it is reasonable to assume that the use of correct denominator and numerators allow us to present the useful and informative etiology data available in these studies.

In conclusion, this systematic review and meta–analysis showed that RSV is the leading cause of ARTIs in China, particularly among infants. Our findings are valuable for guiding the selection of appropriate therapies for ARTIs and implementation of preventive measures against RSV infections. Despite the disease burden, no effective RSV vaccine is currently available. Our data further supports the development of a successful RSV vaccine as a high priority.