The coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic has had exceptional global impacts requiring stringent public health measures known as “lockdowns” [1-3]. Lockdown measures, encompassing publicly enforced home, hospital or workplace quarantine, physical distancing, isolation, and closure of public buildings and educational institutions, have been used to contain infectious diseases but have not been implemented at scale since 1920 [2,4-7]. Infectious outbreaks, including severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS), Middle East respiratory syndrome (MERS), Ebola, swine flu (H1N1), and COVID-19, have reaffirmed such measures as effective in mitigating the destructive potential of infectious diseases, however, may precipitate challenges following their removal [8]. Literature on the immediate impacts of lockdowns and the effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on physical well-being, mental health, and economic climate is rapidly growing [4, 9-11]. Brooks et al have reviewed literature regarding psychological impacts during quarantine, describing considerable mental health burden including anxiety, depression, and post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) symptoms [4]. Closure of workplaces, educational institutions, and leisure activities have significantly disrupted personal and professional pursuits with ensuing lack of social normalcy, loss of academic achievements, and decreased physical activity evoking predictions of persistent ramifications on social functioning and physical health [5,12,13]. Delays in investigations, diagnoses, and treatment have additionally generated concerns regarding indirect morbidity and mortality [14]. As we move beyond the acute phase of the COVID-19 pandemic, the question arises as to what happens when lockdown measures end, for how long impacts persist, and whether certain groups are disproportionately affected. Previous research suggests persistent biopsychosocial consequences up to 3 years after lockdown measures end including effects on mental health with symptoms of anxiety disorders, depression, and PTSD described [15-32]. Social and behavioural repercussions such as discrimination, changes in dietary behaviours, economic effects, and biological impacts including alterations to sleep, biochemical parameters, and weight have additionally been determined [29 ,33-42]. Certain groups including health care workers (HCWs) and those with pre-existing psychiatric conditions have been identified as high-risk [15,17,27,31,32,35,41, 43-45].

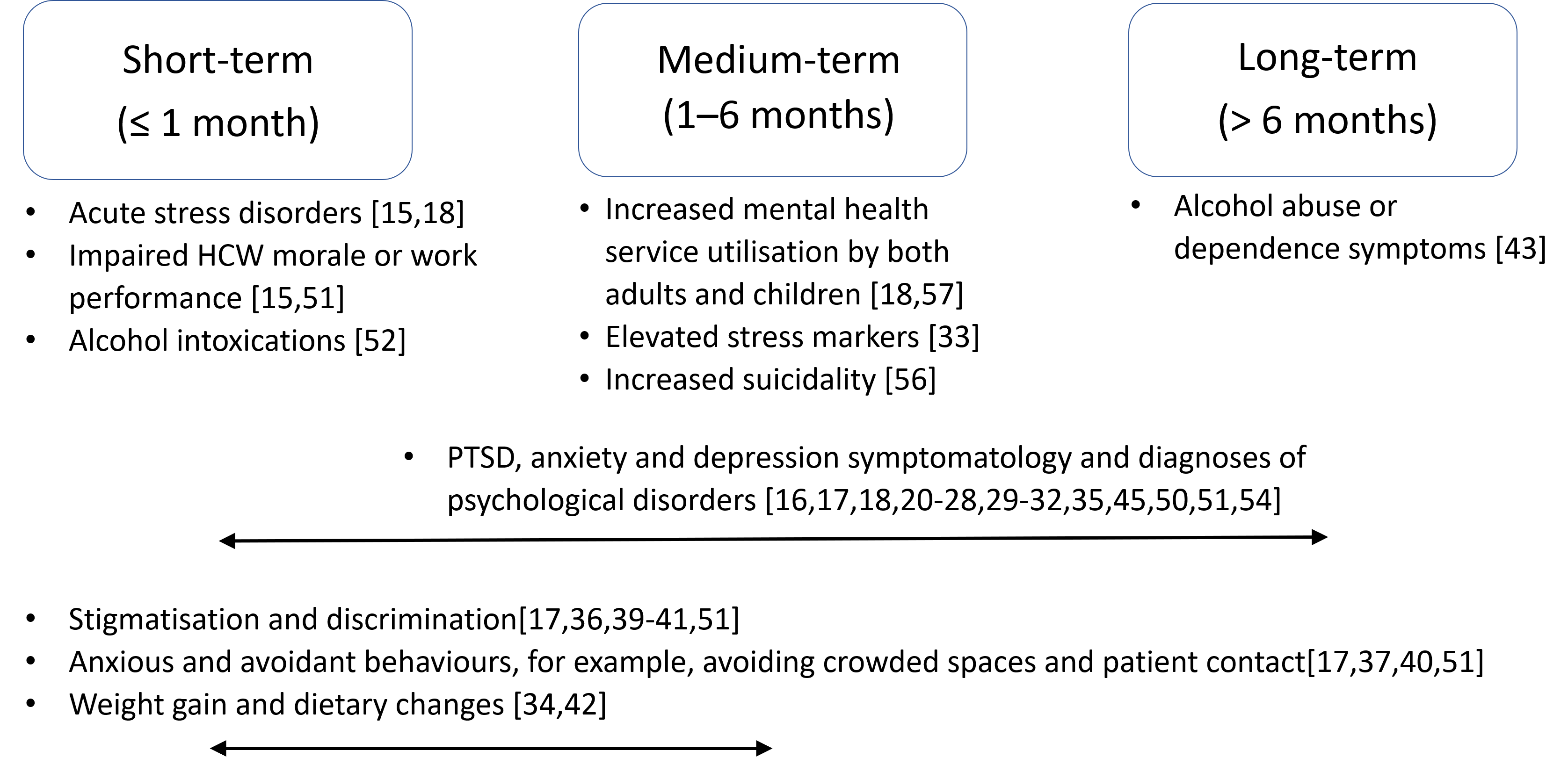

The aim of this systematic review is, for the first time, to comprehensively evaluate biopsychosocial consequences after lockdown measures are lifted and identify strategies to successfully negotiate the transition out of COVID-19 related lockdowns. We hypothesise that lockdown measures can have extensive biopsychosocial consequences, may disproportionately affect certain groups, and could vary according to the time elapsed after their end. To identify what happens following lockdown, and if repercussions vary according to the time passed, this review will categorise outcomes according to short-term, occurring within one month, medium-term from one to six months and long-term after six months. Outcomes will additionally be stratified according to disease outbreak and impacts on families and children are separately described.

Search strategy and selection criteria

The protocol was designed according to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses statement and registered on PROSPERO, CRD42020181134 [ 46]. Two reviewers independently conducted systematic online literature searches from database inception to January 12, 2021, utilising the population, intervention, comparison, outcome framework on PubMed, Ovid MEDLINE, Embase, PsycInfo, Web of Science, and Scopus databases. Search terms are described in Table S1 in the Online Supplementary Document . Studies were filtered to clinical trials, human populations, and languages restricted to English, German, Italian, or French. In the present review, lockdown measures encompassed home, hospital, workplace, dormitory, or camp quarantine, knowing somebody who had been quarantined, social and physical distancing, and national or local closure of public institutions deemed non-essential. Reviewed studies investigated biopsychosocial outcomes after lockdown measures ended including effects on mental health, sleep, weight, biochemical markers, social connectivity, and stigmatisation. The definition of stigmatisation varied from subjective discrimination to objective social ostracization. Lockdown measures must have been implemented following an infectious outbreak, namely SARS, COVID-19, MERS, Ebola, or H1N1. Descriptive studies were included in the absence of a comparator to lockdown measures where these were lacking. Reference lists of identified studies were manually examined. Studies were excluded if they assessed biopsychosocial outcomes exclusively during lockdown measures, involved non-human participants, were review articles, or included populations that exhibited symptoms suggestive of the associated disease.

Data extraction and synthesis

Two reviewers independently identified studies and extracted data to Microsoft Excel (Microsoft Inc, Seattle WA, USA). Discrepancies were discussed and resolved with a third reviewer when a consensus was not established. Authors were contacted for further information where necessary. Significant heterogeneities in study design, lockdown measures, outcomes, and measurement tools prevented I2 calculation and quantitative meta-analysis, therefore narrative synthesis was applied. The ENTREQ statement was utilised [47 ]. Studies were pooled according to time elapsed after lockdown measures ended; namely, short-term ensuing within one month, medium-term arising between one to six months and long-term defined at over one year, disease cause, and outcomes. Timelines for stratification were chosen in agreement with the diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorder criteria for conditions including trauma and stress related disorders (symptom onset within one month), PTSD (duration of disturbance for over one month), and generalised anxiety disorder (symptom duration for at least six months) [ 48]. Symptoms were clustered using international classifications of mental disorders where possible. As few studies examined families and children (defined as under 18 years old), these were described separately. Recommendations for mitigating biopsychosocial effects were made following analysis of risk factors and ordinary interventions.

Bias assessment

The Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool (MMAT) was used by two independent reviewers to determine study quality with a third resolving discrepancies [49]. Quality was calculated using five domains scoring one point per domain achieved to a total of 5, with 5 equating to the highest study quality and 0 the lowest. Study designs were defined as qualitative, quantitative randomised controlled trial, quantitative non-randomised, quantitative descriptive, or mixed methods. Investigated domains for potential bias differed for each study design; however, all included analysis of participant selection, data collection, interpretation, and data reporting. No variation was made to study interpretation based on MMAT scores of 3 or more although study findings scoring 2 were assessed more critically. Studies scoring 0 or 1 were excluded.

Study characteristics

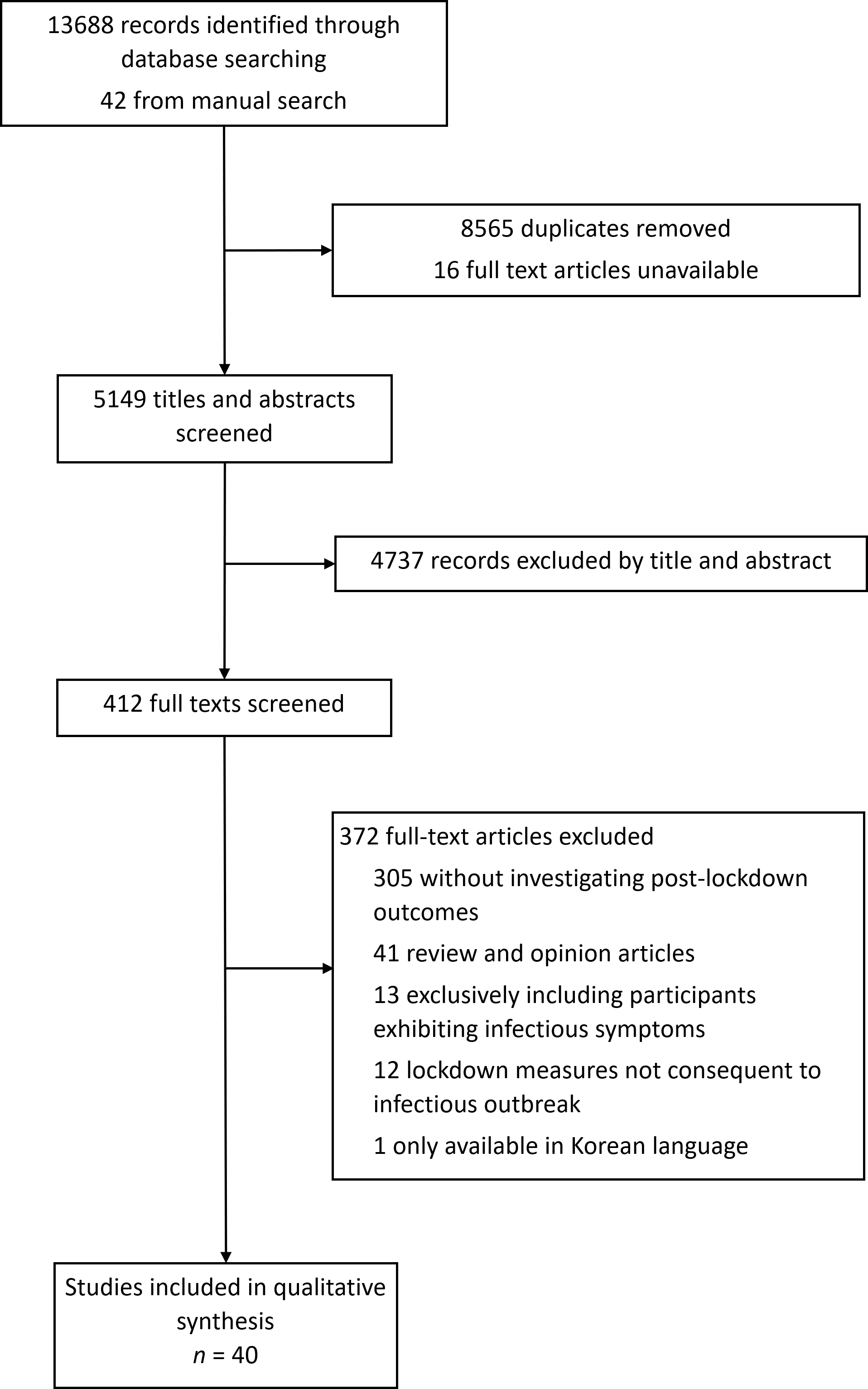

40 studies met inclusion criteria ( Figure 1 ). Study designs comprised cross-sectional (n = 20), longitudinal (n = 10), qualitative (n = 4), cohort (n = 2), mixed methods (n = 2), case report (n = 1), and case-control (n = 1) ( Table 1 ). Data was collected through questionnaire surveys (n = 30), focus groups or interviews (n = 5), biochemical testing (n = 3), audit of service utilisation (n = 1), and case note review (n = 1). Analysed studies assessed outcomes following lockdown measures related to infectious outbreaks, namely SARS (n = 17), COVID-19 (n = 15), MERS (n = 6), Ebola (n = 1), and H1N1 (n = 1). Implemented lockdown measures varied according to disease, country, and participant professional backgrounds, however, included one or a combination of home quarantine (n = 17), national lockdown with social distancing measures (n = 9), workplace quarantine (n = 8), hospital quarantine (n = 7), citywide lockdown (n = 4), workplace closure or suspension of elective surgical procedures (n = 2), dormitory quarantine (n = 1), contact with quarantined individuals (n = 1), and camp isolation (n = 1). Studies sampled diverse age groups (6 to over 65 years), various countries, and differing populations. Sample sizes ranged from 10 to 6231 participants. One study was excluded based on language. No studies scored 0 or 1 using the MMAT. Further studies scored 2 (n = 5), 3 (n = 19), 4 (n = 9), and 5 (n = 7). Where potential biases were evident, these were due to lack of baseline data, confounding factors, variable implementation of lockdown measures, and use of self-reporting as a measurement tool (Appendix S2 in the Online Supplementary Document ).

| Author | Country | Design | Participants | Lockdown measure | Lockdown measure duration | Post-lockdown measure assessment time point* | Disease | Primary outcomes | Measurement tools | Quality rating† |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bai et al (2004) [15] | Taiwan | Cross-sectional | 338 health care workers | Quarantine (type unclear) | 9 days | Up to 10 days | SARS | Acute stress disorder | Study-specific questionnaire adapted from DSM-IV | 3 |

| Cava et al (2005) [39] | Canada | Qualitative | 21 Toronto residents | Home quarantine | 9 days (mean length) | Up to several months | SARS | Stigma, behavioural changes and psychological well-being | Interview | 5 |

| Chandola et al (2020) [50] | UK | Longitudinal | Between 13754 and 17761 adults in the general population | UK national lockdown | 3-4 months | 3-4 weeks | COVID-19 | Common mental disorders | General Health Questionnaire-12 | 4 |

| Chen et al (2007) [44] | Taiwan | Cohort study | 172 hospital staff; 90 health care workers caring for SARS patients and 82 administrative staff | Home quarantine and working non-SARS shifts | 28 days (14 days quarantine, 14 days non-SARS shifts) | 2 weeks | SARS | Physical functioning, role physical, bodily pain, vitality, role emotional, social functioning, general health and mental health | Medical Outcomes Study 36-Item Short Form Survey | 3 |

| Cho et al (2020) [16] | South Korea | Cross-sectional | 67 haemodialysis patients | Home or hospital quarantine in a single room or cohort ward | 14.8 days (mean length) | 1 year | MERS | PTSD | Impact of Event Scale-Revised Korean version | 3 |

| Chong et al (2004) [45] | Taiwan | Cross-sectional | 1257 health care workers, 79 of whom had been quarantined | Dormitory quarantine | 14 days | Up to 7 weeks | SARS | PTSD and mental health | Impact of Event Scale and Chinese Health Questionnaire | 2 |

| Daly & Robinson (2020) [22] | USA | Longitudinal | 7319 nationally representative adults | USA national and state-level lockdown | Variable by state | 1-3 months | COVID-19 | Psychological distress | Patient Health Questionnaire-4 | 5 |

| DiGiovanni et al (2004) [40] | Canada | Qualitative | 1509 Toronto residents, 6 focus groups with 9- 13 persons each | Home quarantine | 10 days | 4 months | SARS | Stigma, behavioural changes and psychological well-being | Focus group | 4 |

| Duy et al (2020) [51] | Vietnam | Cross-sectional | 61 health care workers | Hospital quarantine | 23 days | 6-9 days | COVID-19 | Stigma, depression, anxiety and stress | Study-specific questionnaire adapted from HIV Stigma Scale and Depression, Anxiety and Stress Scale-21 | 4 |

| Grigoletto et al (2020) [52] | Italy | Longitudinal | 338 adolescent and young adult emergency department attendances | Italy national lockdown | 2-3 months | Up to 3 weeks | COVID-19 | Severe alcohol intoxications | Blood alcohol content | 5 |

| Grover et al (2020) [21] | India | Cross-sectional | 144 ophthalmologists | India national lockdown and postponement of elective surgeries | 6 weeks | Up to 2 weeks | COVID-19 | Depression, anxiety and stress | Depression, Anxiety and Stress Scale-21 | 3 |

| Hawryluck et al (2004) [26] | Canada | Cross-sectional | 129 Toronto residents, 88 of whom were health care workers | Home or workplace quarantine | 10 days (median length) | Median 36 days | SARS | PTSD and depression | Impact of Event Scale-Revised and Center for Epidemiological Studies-Depression | 3 |

| Jalloh et al (2018) [25] | Sierra Leone | Cross-sectional | 3564 members of the general population, 1165 of whom had known somebody quarantined | Quarantine (type unclear) | 21 days | Up to 14 months | Ebola | PTSD, anxiety and depression | Impact of Event Scale-Revised and Patient Health Questionnaire-4 | 3 |

| Jeong et al (2016) [27] | South Korea | Longitudinal | 1656 South Korean residents | Home, workplace or hospital quarantine | 14 days | 4-6 months | MERS | Anxiety and anger | General Anxiety Disorder-7 and State-Trait Anger Expression Inventory-2 | 4 |

| Kim et al (2019) [33] | South Korea | Longitudinal | 83 haemodialysis patients and 12 health care workers | Home or hospital quarantine | 17 days | 1 & 3 months | MERS | Physical and emotional stress and haemodialysis efficacy | Multiple plasma biochemical markers | 3 |

| Ko et al (2006) [28] | Taiwan | Cross-sectional | 1499 individuals, 398 of whom exhibited isolated behaviour | Quarantine (type unclear) | Length unclear | 1 months | SARS | Depression | Taiwanese Depression Questionnaire | 2 |

| Koller et al (2006) [53] | Canada | Qualitative | 23; 10 parents, 5 children and 8 health care workers | Hospital quarantine | Length unclear | Up to several months | SARS | Behavioural changes and psychological well-being | Interview | 5 |

| Lee et al (2005) [36] | Hong Kong | Mixed methods | 903 Hong Kong residents | Isolation camp quarantine | 3-4 months | 1-5 months | SARS | Stigma | Study-specific questionnaire | 3 |

| Lee et al (2018) [35] | South Korea | Longitudinal | 359 health care workers working during hospital shutdown and 77 health care workers 1 months following shutdown | Hospital lockdown | 24 days | 1 months | MERS | PTSD | Impact of Event Scale-Revised Korean version | 3 |

| Lei et al (2020) [30] | China | Cross-sectional | 1593 individuals in Southwestern China, 420 of whom had been affected by quarantine | Quarantine (type unclear) | Length unclear | Up to 3 weeks | COVID-19 | Anxiety and depression | Self-rating Anxiety Scale and Self-rating Depression Scale | 4 |

| Li et al (2020) [23] | China | Longitudinal | 173 university students | China national, provincial and citywide lockdowns | 2-3 months | Up to 3 months | COVID-19 | Depression, anxiety, stress and novelty seeking | Depression, Anxiety and Stress Scale-21 and Langer Mindfulness Scale novelty seeking subscale | 3 |

| Liu et al (2012) [31] | China | Cross-sectional | 549 health care workers, 103 of whom had been quarantined | Home or workplace quarantine | Length unclear | 3 years | SARS | Depression | Center for Epidemiological Studies-Depression | 3 |

| Lu et al (2020) [24] | China | Cross-sectional | 1417 Wuhan residents; 387 health care workers and 1035 members of the general population | China national, provincial and citywide lockdowns | 2-3 months | 2 months | COVID-19 | PTSD, anxiety and depression | PTSD Checklist-Civilian version, General Anxiety Disorder-7 and Patient Health Questionnaire-9 | 4 |

| Marjanovic (2007) [37] | Canada | Cross-sectional | 333 nurses | Home or workplace quarantine | Length unclear | Up to 7 months | SARS | Emotional exhaustion, anger and avoidance behaviour | Maslach Burnout Inventory-General Survey, State-Trait Anger Expression Inventory-2 and study-specific questionnaire | 4 |

| Mihashi et al (2009) [54] | China | Cross-sectional | 187; printing company workers, university faculty staff and students | Citywide lockdown | Length unclear | 7-8 months | SARS | Psychological disorders | General Health Questionnaire-30 | 3 |

| Park et al (2020) [38] | South Korea | Cohort study | 116 haemodialysis patients | Home or hospital quarantine in a single room or cohort ward | 15 days (mean length) | 3-6 months | MERS | Clinical parameters and haemodialysis efficacy | Blood pressure and multiple plasma biochemical markers | 3 |

| Ping et al (2008) [43] | China | Cross-sectional | 549 health care workers, 103 of whom had been quarantined | Home or workplace quarantine | Length unclear | 3 years | SARS | Alcohol abuse and dependence | National Household Survey on Drug Abuse | 3 |

| Ping et al (2009) [32] | China | Cross-sectional | 549 health care workers, 103 of whom had been quarantined | Home or workplace quarantine | Length unclear | 3 years | SARS | PTSD | Impact of Event Scale-Revised | 3 |

| Probst et al (2020) [20] | Austria | Longitudinal | 445 adults in the general population | Austria national lockdown | 2-3 months | 1-3 weeks | COVID-19 | Depression | Patient Health Questionnaire-9 | 3 |

| Reynolds et al (2007) [17] | Canada | Cross-sectional | 1057; 269 health care workers, 291 patients, 327 visitors, 139 other | Home or workplace quarantine | 8.3 days (median length) | 1-4 months | SARS | PTSD, stigma, behavioural changes and psychological well-being | Impact of Event Scale-Revised and study-specific questionnaire | 5 |

| Ritish et al (2020) [29] | India | Cross-sectional | 1602 international air passengers | Home or institutional quarantine | 14 days | Up to 1 week | COVID-19 | Anxiety, depression, suicidal ideation and sleep disturbance | Interview | 3 |

| Robertson et al (2004) [41] | Canada | Qualitative | 10 health care workers | Home or workplace quarantine | 10 days | Up to 4 months | SARS | Stigma, behavioural changes and psychological well-being | Interview | 2 |

| Sprang & Silman (2013) [18] | USA & Canada | Mixed methods | 398 parents | Home quarantine and social distancing | Length unclear | 1-6 months | H1N1 & SARS | PTSD | PTSD Checklist-Civilian version and PTSD-Reaction Index | 2 |

| Tan et al (2020) [19] | China | Cross-sectional | 673 workforce members | Workplace closure | 14 days | Up to 1 month | COVID-19 | PTSD, depression, anxiety, stress, insomnia and psychological well-being | Impact of Event Scale-Revised, Depression, Anxiety and Stress Scale-21, Insomnia Severity Index and study-specific questionnaires | 4 |

| Wang et al (2020) [55] | China | Cross-sectional | 1210 individuals in cities across China, 26 of whom had been recently quarantined | Home quarantine | Length unclear | Up to 2 weeks | COVID-19 | PTSD, depression, anxiety and stress | Impact of Event Scale-Revised and Depression, Anxiety and Stress Scale-21 | 3 |

| Yip et al (2010)[56] | Hong Kong | Case-control | 66 elderly suicides; 22 SARS-related, 44 randomly selected controls | Social distancing | Length unclear | Up to 5 months | SARS | Isolation experience, social contact and psychological well-being | Case-note review | 5 |

| Yoon et al (2016)[57] | South Korea | Case report | 6231 Gyeonggi residents | Quarantine (type unclear) | Length unclear | Up to several months | MERS | Mental health service utilisation | Audit | 5 |

| Zarah et al (2020) [42] | USA | Cross-sectional | 3133 American adults | USA national and state-level lockdown | Variable by state | 4 months | COVID-19 | Dietary habits | Study-specific questionnaire | 4 |

| Zhang et al (2020) [34] | China | Longitudinal | 1994 Chinese adults | China national, provincial and citywide lockdowns | 2-3 months | 4 months | COVID-19 | Dietary habits | Study-specific questionnaire | 3 |

| Zhou et al (2020) [58] | China | Longitudinal | 279 Wuhan residents | Citywide lockdown | 2-3 months | Up to 6 weeks | COVID-19 | Depression, psychological need satisfaction, and loneliness | Center for Epidemiological Studies-Depression, Need Satisfaction Scale and Revised Loneliness Scale | 2 |

SARS – severe acute respiratory syndrome, COVID-19 – coronavirus disease 2019, MERS – Middle East respiratory syndrome, H1N1 – influenza A virus subtype H1N1, PTSD – post-traumatic stress disorder, DSM – Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders

*Time points calculated from start of infectious outbreak to data collection period if lockdown measure duration unclear.

†Quality score ranged from meeting none of five criteria (0) to meeting all criteria (5).

Short-term consequences of lockdown measures (≤1 month)

13 studies reported short-term consequences of lockdown with psychiatric symptoms, sleep disturbance, economic aftereffects, behavioural changes, and social repercussions described ( Figure 2 ) [15,19-21,28-30,35,44,50-52,55].

Severe acute respiratory syndrome

Five studies identified short-term repercussions following SARS outbreaks [15,28,36,39,44]. Bai et al found that 17% (7 of 41) of Taiwanese HCWs suffered from an acute stress disorder up to ten days following quarantine compared with 4% (10 of 297) of those not quarantined [15]. Moreover, 20% of quarantined HCWs were reluctant to work compared to 5% not experiencing these measures and were more likely to consider resigning or observed a significant deterioration in their work performance [15]. In contrast, Chen et al described improved physical, social, and emotional well-being in HCWs after two weeks of self-quarantine and a further two weeks of off-duty shifts in comparison to those surveyed immediately after on-duty shifts treating SARS patients [44 ]. However, outcomes remained significantly impaired compared to controls lacking patient contact, particularly for vitality and mental health scores [44 ]. Ko et al associated higher depression symptomatology with being isolated, having poorer family or neighbourhood relationships, and negative economic effects following quarantine [28].

Social repercussions, including stigmatisation, discrimination, behavioural, and emotional reactions were short-term after effects [36,39]. Stigma or discrimination, including interpersonal and professional marginalisation, were experienced by 48∙7% (440 of 903) of individuals returning to work in Hong Kong following quarantine [36]. Canadian participants also reported stigmatisation from colleagues and detailed behavioural changes, including vigorous handwashing and avoidance of crowds [39]. Emotional reactions described by Toronto residents following quarantine comprised initial relief, however, participants expressed unease regarding the effect these measures may have on socially isolated and financially insecure populations [39].

Middle East respiratory syndrome

PTSD symptoms in HCWs were investigated by Lee et al after 24 days of hospital shutdown with 51∙5% (183 of 359) initially meeting diagnostic criteria [35]. One month later, 40∙3% (31 of 77) of survey respondents originally fulfilling criteria remained eligible for PTSD diagnoses [35]. Quarantine itself was not correlated with overall diagnostic scores, however, post-hoc analyses associated higher sleep and numbness sub-scores [ 35].

Coronavirus disease 2019

Psychiatric symptoms, stress, stigmatisation, sleep disturbance, and increased emergency department attendances with alcohol intoxication were identified following COVID-19 lockdown measures [19-21, 29,30,50-52,55].

Eight studies investigated mental health repercussions [19 -21,29,30,50,51,55]. PTSD (10∙8%, 73 of 673), depression (3∙7%, 25 of 673), and anxiety (3∙8%, 26 of 673) symptoms were identified in returning workforces, with symptom prevalence similar to that of the general population at the start of measures [19]. Strict personal and workplace hygiene and attention to employees physical and psychiatric well-being may have mitigated psychological morbidity [19 ]. Acute symptoms of anxiety and depression were identified in six studies [20,21,29,30,50,51]. Lei et al described significantly increased symptoms of anxiety (12.9%, 54 of 420), and depression (22.4%, 94 of 420), in those quarantined, compared to 6.7% (79 of 1173) and 11.9% (140 of 1173) in unaffected individuals respectively [30 ]. Identified risk factors for psychiatric symptoms included stress, loneliness, being female, worse self-perceived health, poor physical health, lower educational levels, lower household income, and those experiencing economic fallout [19-21,30,50]. In contrast, Wang at al found no significant correlation between quarantine and symptoms of PTSD, stress, anxiety, or depression in 26 Chinese residents [55]. Sleep disturbance (4.4%, 71 of 1602), and suicidal ideation (1.9%, 30 of 1602) have been detailed following quarantine and research concerning emergency department attendances found that 11.31% (25 of 221) involved severe alcohol intoxication in the three weeks after lockdown compared to 0.88% (1 of 117) in the preceding period [29, 52].

Social repercussions, including stigma and behavioural modifications, have been investigated in HCWs [51]. Duy et al reported 34.43% (21 of 61) expressed guilt for isolating, 18.03% (11 of 61) felt unsafe in their profession, and many described discriminatory experiences [51]. However, only 1.64% (1 of 61) detailed undertaking efforts to avoid COVID-19 related work after quarantine [51].

Medium-term consequences of lockdown measures (1-6 months)

Symptoms of depression, anxiety, and trauma and stressor related disorders have been identified as medium-term after-effects following lockdown [17,22-24,26,27,45,48]. Behavioural and emotional repercussions, social exclusion, stigmatisation, changes to inpatient biochemical markers, weight, and dietary behaviours have also been established to occur one to six months after lockdown measures ended [17,33, 34,36-38,40-42].

Severe acute respiratory syndrome

Three studies investigated medium-term PTSD symptoms following the SARS outbreak [17,26,45]. Hawryluck et al and Reynolds et al found that following Toronto-based home or workplace quarantine the prevalence of significant PTSD symptomatology was 28∙9% (35 of 129) and 14∙6% (148 of 1057) respectively [17,26]. Chong et al, however, found no correlation between quarantine and PTSD or psychiatric morbidity in Taiwanese HCWs [ 45]. Symptoms of depression and suicidal ideation were associated with quarantine [ 26,56]. Hawryluck et al described significant depression symptoms in 31∙2% of their cohort [26]. Although precise time-frames are unclear, one case-note review described increased suicide rates in those aged over 65 during and in the months after the SARS outbreak in Hong Kong with measures including reduced interpersonal contact, disruptions to social support, and experiences of disconnection highlighted as contributing factors [56]. Identified risk factors for symptoms of PTSD and depression included quarantine periods longer than ten days and lower household income [26]. Despite governmental compensation, Reynolds et al associated quarantine with household income reduction [17].

Behavioural changes and emotional reactions were observed [17 ,37,40]. Reynolds et al found that 53∙7% (568 of 1057) avoided those sneezing or coughing, whilst 25∙7% (272 of 1057) refrained from entering crowded public spaces up to four months after lockdown [17]. Individuals continued performing behaviours, including frequent hand washing, and several participants reported extending their quarantine or limiting social contact beyond public guidance [17,40]. A study involving nurses associated avoidance coping behaviours, including missing work and avoiding patient contact, with home or workplace quarantine [37]. Increased anger correlated with longer lengths of quarantine, although emotional exhaustion was not associated [37].

Stigmatisation following quarantine was reported in four studies [17,36,40,41]. Experiences ranged from heightened attention to social ostracization in settings including day-care facilities, workplaces, and private social gatherings, leading some HCWs to deny their occupation or conceal they had quarantined [17, 40,41]. However, perceived discrimination reduced to 4∙0% (36 of 903) from 48∙7% (440 of 903) for residents in Hong Kong three months after lockdown measures ended compared to immediately after quarantine [36].

Middle East respiratory syndrome

Symptoms of anxiety, requirements for psychiatric support, and changes to biochemical parameters are identified medium-term consequences following the MERS outbreak in South Korea [27,33,38,57].

A study quantifying mental health service utilisation by those quarantined demonstrated that 19∙6% (1221 of 6231) experienced psychological and emotional difficulties during quarantine, with 28∙7% (350 of 1221) of these requiring follow-up after measures ended [ 57]. Jeong et al described 7∙6% (126 of 1656) of residents reporting anxiety symptoms during isolation, decreasing to 3∙0% (50 of 1656) four to six months later, similar to general population prevalence [ 27]. Factors associated with increased anxiety symptoms included insufficient supply provision, lacking access to social networking facilities, psychiatric comorbidities, and financial concerns [27].

Two studies investigated biological parameters in haemodialysis patients during and after quarantine or isolation [33,38]. One study reported impaired haemodialysis efficacy and albumin levels during isolation which significantly improved three months later [38]. Another study reported normal haemodialysis efficacy, however, detected continuously elevated stress markers in patients compared to HCWs quarantined alongside them [33].

Coronavirus disease 2019

Repercussions for psychological well-being, dietary habits, and weight have been identified medium-term outcomes following COVID-19 lockdown measures [22 -24,42].

Psychological distress, comprising symptoms of depression and anxiety disorders, was found to increase during measures for American participants with or without mental health diagnoses [ 22]. Although levels of distress returned to baseline in both cohorts after measures ended, initial distress severity was significantly higher in those with pre-existing psychiatric diagnoses [22]. Symptoms of anxiety, PTSD, and depression were identified during lockdown in the general public and HCWs by Lu et al, with HCW PTSD (16.2%, 62 of 382) and any depression (57.9%, 221 of 382) symptomatology significantly higher compared to general population prevalence, (11.7%, 121 of 1035) and (45.7%, 473 of 1035) respectively [24]. Similarly, overall symptom predominance decreased following measures lifting [24]. Conversely, symptoms of stress, anxiety, and depression in a study of Chinese students decreased during national lockdown, and subsequently increased after measures were removed [23]. Minimal changes to psychological well-being were described by Zhou et al six weeks after national lockdown ended in China [58].

Two studies described consequences to dietary behaviours and weight [34,42]. Over half of respondents in one study (n = 1994) reduced their consumption of seafood, raw food, and imported frozen food whilst increasing the frequency of home-cooking after lockdown in China [34]. Several participants also continued engaging in unhealthy dietary behaviours including drinking vinegar (9.8%, 195 of 1994) to prevent infection [34]. Zarah et al found that although most American respondents did not report dietary changes following lockdown, 38% (1191 of 3133) described weight gain, and increased consumption of sweets and salty snacks were nevertheless noted [42].

Long-term consequences of lockdown measures (>6 months)

Psychological distress, alcohol abuse/dependence and financial concerns have been described to persist over six months after lockdown measures end [16,25,31,32,43,54]. Several at-risk groups for long-term psychological morbidity were identified [16,25,31,32 ,43,54].

Severe acute respiratory syndrome

Three studies analysed survey responses from HCWs, 18∙8% (103 of 549) of whom were quarantined, three years following the SARS outbreak in Beijing [31,32,43]. Quarantine was significantly associated with increased alcohol abuse/dependence, PTSD, and depression symptoms [31,32,43]. Identified groups at-risk for exhibiting PTSD symptoms over six months after measures ended were HCWs who experienced prolonged contact with infectious patients or those who had close relations diagnosed with SARS [32]. Risk factors for depression symptoms included concurrent PTSD symptoms, work-related stressors, being single, and prior experiences of traumatic events [31]. Mihashi et al measured the prevalence of psychological disorders in printing company workers, university staff, and students during and after hospital isolation or home quarantine [54]. During these measures, 24∙6% (46 of 187) reported symptoms indicating psychological disorder increasing to 26∙2% (49 of 187) seven to eight months later, however, this did not achieve statistical significance [54]. Income reduction was identified as the principally associated risk factor [54].

Middle East respiratory syndrome

Significant long-term PTSD symptoms were identified in 17∙9% (12 of 67) of quarantined haemodialysis patients in South Korea, however, lengths of isolation of 16 days or more were associated with lower symptomatology [16]. Females were also at higher risk of exhibiting PTSD symptoms over six months after lockdown measures ended [ 16].

Ebola

Another study investigated PTSD, anxiety, and depression symptomatology in 3564 residents in Sierra Leone approximately 14 months after the start of the Ebola outbreak [25]. Knowing somebody who had been quarantined or having personal relations with suspicion or diagnosis of Ebola was independently associated with increased PTSD, anxiety, and depression symptoms [25]. Higher and ongoing perceived disease threat was also associated with symptom prevalence [25].

Impacts of lockdown measures on primary caregivers and children

Social and psychological consequences in families and children were evident following SARS and H1N1-related quarantine [18, 53]. A third of primary caregivers, surveyed approximately one to six months after quarantine or isolation, reported their children began utilising mental health services during or after measures [18]. Diagnoses including generalised anxiety disorder, acute stress disorder, adjustments disorder, grief, and PTSD [18]. 28% (27 of 98) of quarantined parents met diagnostic cut-offs for PTSD compared to 5∙8% (17 of 299) not quarantined, whilst 30% of children also met diagnostic criteria [18]. Significant associations between children experiencing containment measures, paediatric PTSD symptoms, and parents concurrently displaying PTSD symptoms were found [18]. A qualitative study of parents and children described children developing anxious behaviours including increased signs of distress when parents left for work two months after hospital isolation [53 ].

What have we learned from previous lockdown measures and what are the implications for current lockdown measures?

Principal findings

Lockdown measures are a venerable method to contain infectious disease outbreaks, however, profound biopsychosocial impacts, ranging from acute stress reactions to chronic psychopathology, are apparent [7]. Economic repercussions may be compounded by social obstacles in returning to work ( Table 2 ) [26-28, 39]. Certain groups, such as those lacking financial security, are therefore particularly vulnerable to continued financial hardship [22,26-28,30,39,50,54]. Enduring behavioural and social effects and adjustments to workplace practice can impede return to social and professional normalcy which may require extensive support including workplace modifications [15,17,28,37,39-41,51]. Acute alcohol intoxication, weight gain, and dietary changes have also been described [34,42 ,52]. Physical, emotional, and social well-being of HCWs during outbreaks may improve following self-quarantine compared to parameters observed during clinical work [44]. However, no differences in the degree of psychiatric symptoms in other workforces following COVID-19 measures were found [19]. National interventions to alleviate individually perceived disease threat and improve social support may reduce psychological morbidity [25,28,56]. Actively approaching vulnerable individuals and ensuring publicly accessible mental health services may reduce and prevent mental health burden [19,28]. However, comprehensive research analysing effective interventions to mitigate biopsychosocial aftereffects of lockdown is lacking.

| Tailored interventions according to time-elapsed, including acute psychological support and longer-term management targeting maladaptive coping mechanisms [15,16,18 ,25,27,31,32,34 ,35,39,41,43,45 ,57] |

| Early identification and active follow-up of high risk and vulnerable groups [16-22,25 -28,30-32,35,39 ,43,50,53,54] |

| Public health authorities to deliver clear and accurate information and educational resources [ 17,19,26-28,36,39 -41,54,55] |

| Provision of financial aid, supplies, and hygiene-enhancing policies [17,19,25 ,27,30,39,40,54 ,55] |

| Employer attention to employees’ physical and psychological well-being [19,26,36 ,37,40,51] |

| Promotion of social connectivity, networking, and support [20,25,27,28,53 ,56] |

Previous studies

Brooks et al reviewed psychological consequences of quarantine primarily focusing on interventions and outcomes during quarantine [4 ]. Acute stress reactions, PTSD, anxiety, and depression symptoms were identified [4]. Behavioural changes, reluctance to re-enter work, and deteriorating work performance were also described [4]. Financial loss consequent to quarantine was an evident stressor for psychological well-being [ 4]. Brooks et al highlighted the importance of social networking facilities in avoiding frustration, boredom and anxiety, and emphasised the importance of clear public health messages [4 ]. Recent evidence indicated that measures introduced in China, including city-wide lockdown, swift isolation of confirmed and suspected cases, effective contact tracing, and workplace adjustments likely helped improve public confidence [ 19,30]. Brooks et al additionally reported that stigmatisation following quarantine could be ameliorated through public education [4].

Previous reviews had not investigated suicidality, biological markers including biochemical parameters and weight change, dietary behaviours, or psychiatric symptoms in returning workforces after lockdown measures. The importance of social support, relationships, and their correlation with mental health well-being have also not been addressed. Social barriers compounding financial hardship, the implications of perceived disease risk, and the significance of childhood isolation from primary caregivers were similarly unexamined. This review exclusively explored repercussions once lockdown measures were lifted. To our knowledge, this is also the first review to report a possible restorative effect of quarantine in HCWs by improving emotional, physical, and social well-being.

Implications

Individualised, accessible, and timely support delivered on multidimensional platforms focusing on short, medium, and long-term consequences may restrict psychological distress, economic repercussions, stigmatisation, and assist high-risk groups. Identified at-risk groups include those with pre-existing psychiatric diagnoses, children, elderly, HCWs, socially isolated individuals, and hospital inpatients. Short to medium-term interventions may require acute psychological support directed at trauma processing. Medium to long-term repercussions could necessitate approaches reforming maladaptive coping mechanisms, behaviours including substance misuse, and addressing psychological morbidity, particularly PTSD and depression. Prioritising early public education may prevent short to medium-term stigmatisation of quarantining individuals. Economic adversity can have profound short and long-term effects therefore financial support, modification of work environments, and encouraging employment could enable financial rehabilitation and prevent mental health sequela. Actively identifying and directing services towards vulnerable groups could similarly prevent psychological morbidity. Social connectedness, known to enhance health, may require tailored communication initiatives to promote re-integration to social and professional activities following lockdown measures [59]. Arranging sufficient social support and ensuring access to essential items, could additionally mitigate negative outcomes.

Strengths and limitations

This review includes studies from a range of infectious outbreaks including SARS, MERS, Ebola, H1N1 and COVID-19. The present review incorporated a comprehensive search strategy, manual analysis of references lists, and inclusion of several languages. Multiple researchers employed independent study identification and data extraction reducing bias and increasing study yield.

Despite these strengths, most eligible studies were cross-sectional and mainly comprised research examining SARS and COVID-19 outbreaks. Diversity in disease-cause and consequently applied lockdown measures presented significant heterogeneity, occasionally involved small sample sizes, and investigated specific populations from diverse cultural backgrounds and professions which may yield results not widely applicable or comparable. Notably, at the time of writing the COVID-19 pandemic was ongoing with lockdown measures varying by country and region albeit with temporary easing and tightening according to fluctuating infection rates. Variations in outcomes and measurement tools may have produced unstandardised diagnostic symptom identification. Comparators were not always included by reviewed studies, and research on other lockdown measures including mandatory use of masks and school closures, were rare or unavailable. No randomised controlled trials were identified. Given the evolution, fluctuating lockdown measures, and unprecedented nature of the COVID-19 pandemic, the relevance of past interventions and outcomes are difficult to predict. While consequences of lockdown measures have been described, the biopsychosocial impact of not implementing such measures in a randomised trial is ethically challenging in a research environment hence leaving retrospective analysis as the most pragmatic option.

Future research

Whilst there is strong evidence that the end of lockdown will be accompanied by harmful biopsychosocial effects, randomised controlled trials of preventive measures are lacking. Further research defining high risk groups and investigating tailored preventive approaches is needed. Further pandemics in addition to resurgences of COVID-19 are expected, therefore researching mitigating effects of future lockdowns is urgently required.

COVID-19 lockdown measures are unprecedented and have highlighted the need to rapidly produce high-quality research evaluating the effectiveness of actions and identifying further consequences. Establishing research in the eventuality of future lockdown periods is crucial to producing an evidence base that can inform decisions and recommendations. Lockdown can be traumatic, provoke mental health deterioration, induce financial hardship, and repercussions for social and behavioural conduct may impede social connectedness and impact professional practice. Offering support tailored to short, medium, and long-term consequences may help overcome acute and persisting hardship and prevent psychological morbidity. Establishing relevant research informing prompt, coherent, and consistent public health guidance and social support could be essential in mitigating negative outcomes following lockdown measures.